Todays ZamanIraqi Kurds consider oil a guarantee for independence Kurds, who are taking decisive steps to advance the dream of an independent state nowadays, consider the oil under the areas they control as an essential factor in consolidating Kurdish sovereignty over the region and a chance to rewrite Kurdish history in the region.

Kurds, who are taking decisive steps to advance the dream of an independent state nowadays, consider the oil under the areas they control as an essential factor in consolidating Kurdish sovereignty over the region and a chance to rewrite Kurdish history in the region.Oil has always been central to the Kurdish apriration for international legitimacy. Kurds consider oil a crucial element for international oil trade in the future; therefore, they are struggling over the control of the oil-rich areas in both Syria and Iraq. With a population of around 30 million, Kurds are an ethnic minority group dispersed throughout Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

In Syria, there is a fierce fight between the Democratic Union Party (PYD) -- a Syrian offshoot of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) -- and other groups over the control of the oil-rich areas. Last year, PYD leader Saleh Muslim Muhammad stated that 60 percent of the oil is controlled and administered by Kurds in Syria. There were even reports saying that the PYD was in talks with Turkey to discuss the export of oil.

In Iraq, Kurds have been in charge of their own affairs since the Gulf War in 1991. Iraqi Kurds run their own autonomous and relatively prosperous region in northern Iraq; furthermore, they have their own army and pursue their own foreign policy. Iraq's Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is eager to export the oil in their region as they consider it an opportunity to realize their long-held aspirations for independence.

From the other side, as a growing country Turkey desperately needs energy, and the KRG appears to be one of the best options for Turkey's energy needs. The two sides have signed energy deals to further improve economic relations.

However, the biggest risk in this picture is that Turkey's economic ties with the KRG, particularly related to oil, have raised eyebrows in Baghdad. The government has stressed that Turkey should ask the Iraqi government before taking any action in the region that may led to fragmentation in the country.

Beril Dedeoğlu of Galatasaray University told Sunday's Zaman that Turkey would like to see no tension between Baghdad and Arbil over oil, but on the other hand, it seeks to import oil from the Kurds. “This is the game that Turkey wants to play. However, it is unclear whether this game will be sustainable. When at a fork in a road, Turkey will side with the Kurds, not with Baghdad,” she explained.

However, another risk is that the KRG would seek full independence because of its energy deal with Turkey and other foreign companies, despite Baghdad's concerns. However, experts believe that Turkey will act on this matter with an understanding of the risks.

Needless to say, oil is at the heart of the dispute between Kurds in the north and the central government in Baghdad. Under the Iraqi Constitution, Kurds are allotted 17 percent of Iraq's total revenue, 95 percent of which is oil-related; but it must turn over oil discovered and drilled in its territory. But, despite Baghdad's concerns, the KRG considers the oil pipeline to Turkey -- which was completed in 2013 -- as a tool for greater independence.

Recent remarks made by KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani garnered great attention, as he signaled that the export of oil is significant for Kurds in gaining independence in the future and that whatever the Baghdad thinks, Kurds are determined to sell this oil.

Barzani said Arbil will start selling its stored oil at the Turkish port of Ceyhan, with or without Baghdad's consent, in the beginning of May. Barzani clearly remarked: “We will sell it. That is our decision.”

In an exclusive interview with Rudaw news outlet, Barzani was asked whether Kurds had prepared themselves to sell oil without Iraq's consent. Barzani replied, “Yes, and we already have paid the price for it.”

Meanwhile, Turkish Energy Minister Taner stated on Wednesday that Turkey is not currently a customer for Kurdish oil but; however, adding that Turkish companies have deals with the KRG and that Kurds could sell the oil to the private sector in Turkey.

For Kurds, oil represents 'hope, but also a bed of nails'Iraqi Kurds' close economic relations with Ankara would have been unthinkable a few years ago, when Ankara enjoyed strong ties with Iraq's central government in Baghdad and was deep in a decades-long fight with Kurdish terrorists on its own soil.

“Turkey gradually understood that it is in our mutual interest. We negotiated for nearly two years until we reached an agreement and signed a protocol on energy cooperation between Turkey and the KRG. This protocol allows the KRG to export its oil to Turkey and the outside world,” said Barzani.

The pipeline is also likely to take the already warm political and economic relations between Iraqi Kurdistan and neighboring Turkey to new heights. Kurdish officials say they plan to reach a production target of 2 million barrels per day by 2015. If that target is achieved, the Kurdistan region will become a major player on the international energy map. Kurdish oil reserves are estimated at around 45 billion barrels.

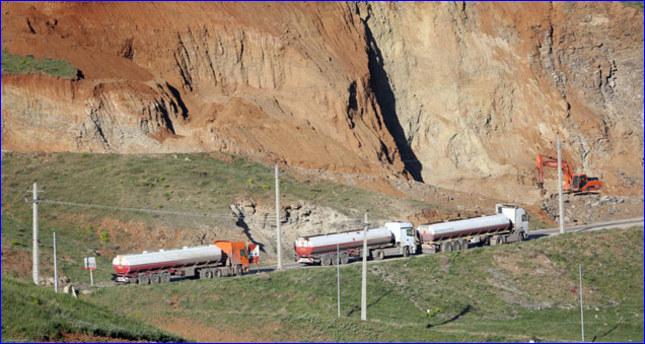

When asked about the amount of oil currently being exported to Turkey, Barzani replied that 1.5 million barrels had been sent to Ceyhan, where it is stored in tanks set aside for Kurdistan's oil, but that is still part of Iraqi storage. The KRG's pipeline carries the Kurdish oil to Turkey's Mediterranean export hub of Ceyhan. It initially carries heavy oil from the Tawke field and connects with the 40-inch-wide existing Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline to be exported to world markets.

Regarding relations with Turkey, Barzani said that Arbil recognizes its neighbor's importance. “Turkey, for us, is the gateway to the West,” he said.

According to Dedeoğlu, oil is an important factor considered by the Kurds for their dream of independence; however, it is also dangerous in that it brings Kurds face-to-face with the Baghdad administration. She describes oil for Kurds as: “On one hand, it is a [beacon of] hope, but on the other, it is like a bed of nails.”

When Barzani was asked whether selling oil independently was a step toward Kurdish independence, he replied: “This requires the patience and endurance of the people and political parties of the KRG. If the political parties and people in the KRG are not united and do not have one voice on this issue, we won't be able to succeed. The future of the KRG is tied to this subject.”

http://www.todayszaman.com/news-346688- ... dence.html