Welcome To Roj Bash Kurdistan

Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advice

Re: Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advic

UK post lock-down plans

Gyms and non-essential shops in all areas are expected to be allowed to reopen when England's lockdown ends

On Monday afternoon, Boris Johnson will explain the detail of England's return to the "three-tier system" when lockdown ends on 2 December.

It is reported pubs in tier three will stay shut except for takeaway. In tier two, only those serving meals can open.

Last orders in all pubs will remain at 22:00 GMT, but customers will have an extra hour to drink up.

The ban on outdoor grassroots sport is also set to be lifted in all tiers, following calls for this restriction to be eased.

And mass testing will be introduced in all tier three areas.

Details of which tier every region of England will be put into are expected on Thursday.

More areas are set to be placed in the higher tiers - high risk or very high risk - after lock-down.

Gyms and non-essential shops have been closed in England since 5 November, but are expected to reopen in all areas. Gyms were previously allowed to open in tier three, despite initially being told to shut in some places.

What will we be allowed to do at Christmas?

The prime minister had hoped to announce arrangements for the Christmas period on Monday, but this has been delayed until at least Tuesday to allow the Scottish and Welsh governments to agree the plans.

It comes after the Westminster government said the UK's four nations had backed plans to allow some household mixing "for a small number of days" over Christmas.

One option that was discussed in meetings this weekend was that three households could be allowed to meet up for up to five days, according to the BBC's deputy political editor Vicki Young.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told BBC Radio 4's Today programme the government hoped to agree a "cautious, balanced approach" for Christmas "that can allow people to see their families, but also makes sure that we can keep the virus under control".

Coronavirus in the UK

Mr Johnson is expected to tell the House of Commons later: "The selflessness of people in following the rules is making a difference."

The increase in new cases is "flattening off" in England following the introduction of the nationwide lock-down measures, he will say.

The prime minister will say "we are not out of the woods yet", with the virus "both far more infectious and far more deadly than seasonal flu".

"But with expansion in testing and vaccines edging closer to deployment, the regional tiered system will help get the virus back under control and keep it there," he will say.

Cases chart

The plan for extensive community testing in tier three areas follows a pilot programme in Liverpool, where more than 200,000 people were tested and which the government said contributed to the fall in cases there.

Mr Johnson is expected to tell MPs that rapid testing will "help get the virus back under control and keep it there".

Daily coronavirus tests will be offered to close contacts of people who have tested positive in England, as a way to reduce the current 14-day quarantine.

Downing Street also said weekly testing would be expanded to all staff working in food manufacturing, prisons and the vaccine programme from next month.

On Sunday, the UK recorded another 18,662 confirmed coronavirus cases and 398 deaths within 28 days of a positive test. The total includes 141 deaths which were omitted from the 21 November figures in error.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-55038155

Gyms and non-essential shops in all areas are expected to be allowed to reopen when England's lockdown ends

On Monday afternoon, Boris Johnson will explain the detail of England's return to the "three-tier system" when lockdown ends on 2 December.

It is reported pubs in tier three will stay shut except for takeaway. In tier two, only those serving meals can open.

Last orders in all pubs will remain at 22:00 GMT, but customers will have an extra hour to drink up.

The ban on outdoor grassroots sport is also set to be lifted in all tiers, following calls for this restriction to be eased.

And mass testing will be introduced in all tier three areas.

Details of which tier every region of England will be put into are expected on Thursday.

More areas are set to be placed in the higher tiers - high risk or very high risk - after lock-down.

Gyms and non-essential shops have been closed in England since 5 November, but are expected to reopen in all areas. Gyms were previously allowed to open in tier three, despite initially being told to shut in some places.

What will we be allowed to do at Christmas?

The prime minister had hoped to announce arrangements for the Christmas period on Monday, but this has been delayed until at least Tuesday to allow the Scottish and Welsh governments to agree the plans.

It comes after the Westminster government said the UK's four nations had backed plans to allow some household mixing "for a small number of days" over Christmas.

One option that was discussed in meetings this weekend was that three households could be allowed to meet up for up to five days, according to the BBC's deputy political editor Vicki Young.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told BBC Radio 4's Today programme the government hoped to agree a "cautious, balanced approach" for Christmas "that can allow people to see their families, but also makes sure that we can keep the virus under control".

Coronavirus in the UK

Mr Johnson is expected to tell the House of Commons later: "The selflessness of people in following the rules is making a difference."

The increase in new cases is "flattening off" in England following the introduction of the nationwide lock-down measures, he will say.

The prime minister will say "we are not out of the woods yet", with the virus "both far more infectious and far more deadly than seasonal flu".

"But with expansion in testing and vaccines edging closer to deployment, the regional tiered system will help get the virus back under control and keep it there," he will say.

Cases chart

The plan for extensive community testing in tier three areas follows a pilot programme in Liverpool, where more than 200,000 people were tested and which the government said contributed to the fall in cases there.

Mr Johnson is expected to tell MPs that rapid testing will "help get the virus back under control and keep it there".

Daily coronavirus tests will be offered to close contacts of people who have tested positive in England, as a way to reduce the current 14-day quarantine.

Downing Street also said weekly testing would be expanded to all staff working in food manufacturing, prisons and the vaccine programme from next month.

On Sunday, the UK recorded another 18,662 confirmed coronavirus cases and 398 deaths within 28 days of a positive test. The total includes 141 deaths which were omitted from the 21 November figures in error.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-55038155

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 28437

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advic

Oxford University vaccine

is highly effective

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is currently in the final stages of testing

The coronavirus vaccine developed by the University of Oxford is highly effective at stopping people developing Covid-19 symptoms, a large trial shows.

Overall results showed 70% protection, but the researchers say the figure may be as high as 90% by tweaking the dose.

The results will be seen as a triumph, but also come off the back of Pfizer and Moderna showing 95% protection.

However, the Oxford jab is far cheaper, and is easier to store and get to every corner of the world than the other two.

So the vaccine will play a significant role in tackling the pandemic, if it is approved for use by regulators.

"The announcement today takes us another step closer to the time when we can use vaccines to bring an end to the devastation caused by [the virus]," said the vaccine's architect Prof Sarah Gilbert.

The UK government has pre-ordered 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine and AstraZeneca says it will make three billion doses for the world next year.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it was "incredibly exciting news" and that while there were still safety checks to come, "these are fantastic results".

The vaccine has been developed in around 10 months, a process that normally takes a decade.

What did the trial show?

More than 20,000 volunteers were involved, half in the UK, the rest in Brazil.

There were 30 cases of Covid in people who had two doses of the vaccine and 101 cases in people who received a dummy injection.

When volunteers were given two "high" doses the protection was 62%, but this rose to 90% when people were given a "low" dose followed by a high one. It's not clear why there is a difference.

"We're really pleased with these results," Prof Andrew Pollard, the trial's lead investigator, told the BBC.

He said the 90% effectiveness data was "intriguing" and would mean "we would have a lot more doses to distribute."

There were also lower levels of asymptomatic infection in the low-followed-by-high-dose group which "means we might be able to halt the virus in its tracks," Prof Pollard said.

When will I get it?

In the UK there are four million doses ready to go, with another 96 million to be delivered.

But nothing can happen until the vaccine has been approved by regulators who will assess the vaccine's safety, effectiveness, and that it is manufactured to high standard. This process will happen in the coming weeks.

However, the UK is ready to press the go button on an unprecedented mass immunisation campaign that dwarfs either the annual flu or childhood vaccination programmes.

Care home residents and staff will be first in the queue, followed by healthcare workers and the over-80s. The plan is to then to work down through the age groups.

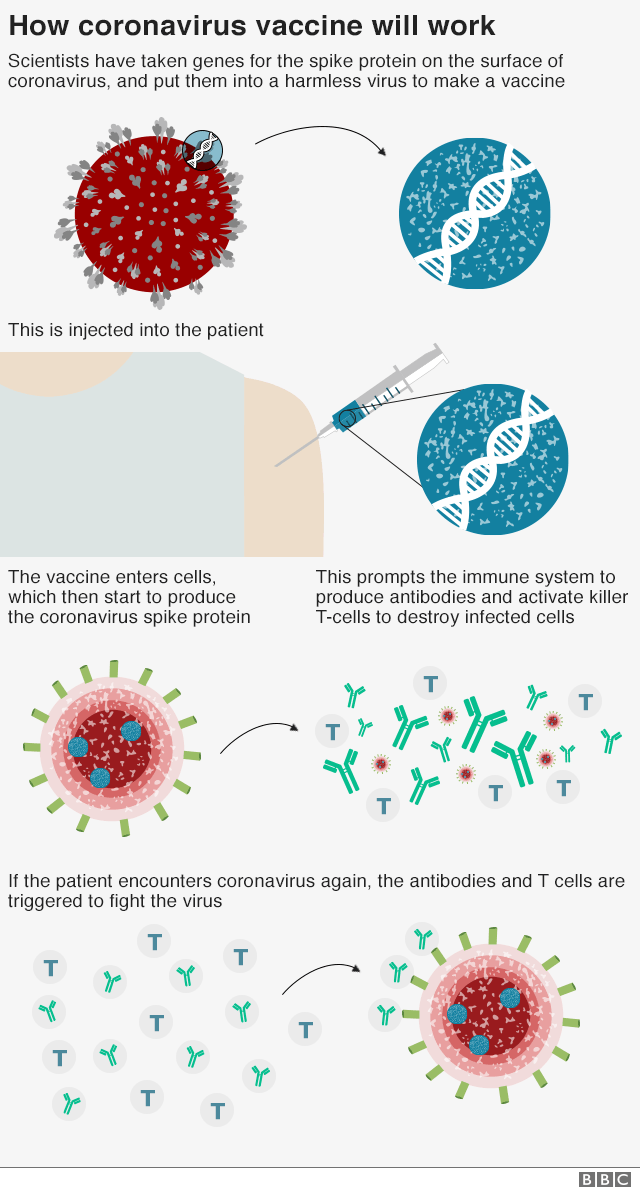

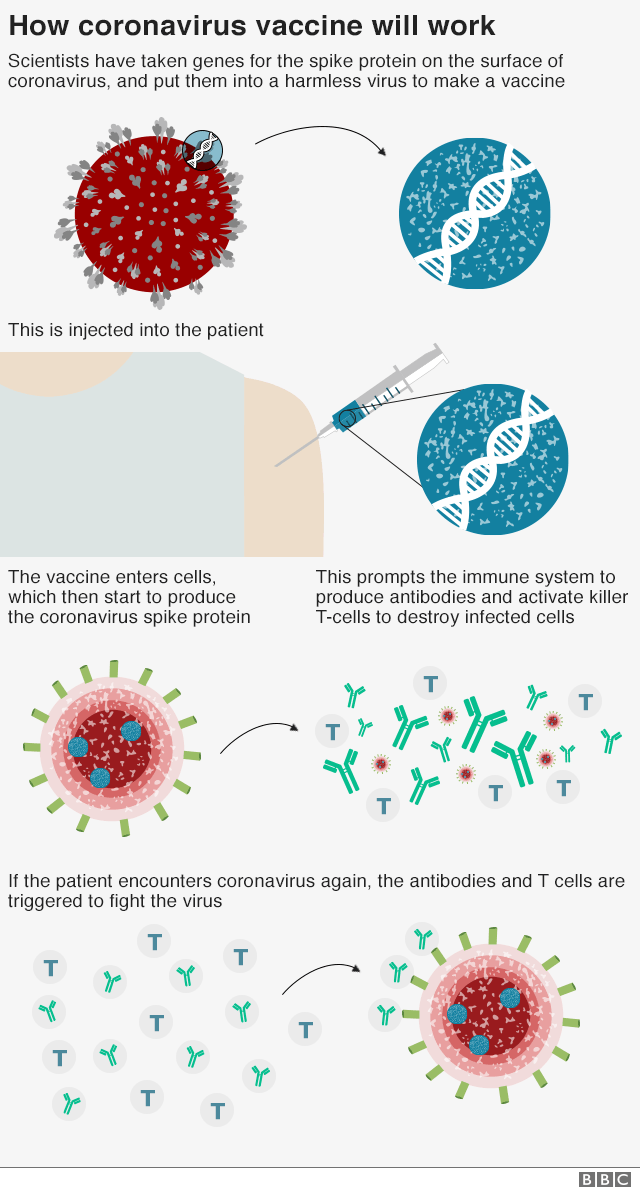

How does it work?

The vaccine is a genetically modified common cold virus that used to infect chimpanzees.

It has been altered to stop it causing an infection in people and to carry the blueprints for part of the coronavirus, known as the spike protein.

Once these blueprints are inside the body they start the producing the coronavirus' spike protein, which the immune system recognizes as a threat and tries to squash it.

How the coronavirus vaccine works:

After Pfizer and Moderna both produced vaccines delivering 95% protection from Covid-19, a figure of 70% will be seen by some as relatively disappointing.

However, anything above 50% would have been considered a triumph just a month ago and 70% is comfortably better than the seasonal flu jab.

This is still a vaccine that can save lives from Covid-19.

It also has crucial advantages that make it easier to use. It can be stored at fridge temperature, which means it can be distributed to every corner of the world, unlike the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, which need to be stored at much colder temperatures.

Oxford's manufacturing partner, AstraZeneca, is preparing to make three billion doses worldwide.

The Oxford vaccine, at a price of around £3, also costs far less than Pfizer's (around £15) or Moderna's (£25) vaccines.

What difference will this make to my life?

A vaccine is what we've spent the year waiting for and what lockdowns have bought time for.

However, producing enough vaccine and then immunising tens of millions of people in the UK, and billions around the world, is still a gargantuan challenge.

Life will not return to normal tomorrow, but the situation could improve dramatically as those most at risk are protected.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told BBC Breakfast we would be "something closer to normal" by the summer but "until we can get that vaccine rolled out, we all need to look after each other".

What's the reaction been?

Prof Peter Horby, from the University of Oxford by not involved in the trial, said: "This is very welcome news, we can clearly see the end of tunnel now. There were no Covid hospitalisations or deaths in people who got the Oxford vaccine."

Dr Stephen Griffin, from the University of Leeds, said: "This is yet more excellent news and should be considered tremendously exciting. It has great potential to be delivered across the globe, achieving huge public health benefits.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55040635

is highly effective

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine is currently in the final stages of testing

The coronavirus vaccine developed by the University of Oxford is highly effective at stopping people developing Covid-19 symptoms, a large trial shows.

Overall results showed 70% protection, but the researchers say the figure may be as high as 90% by tweaking the dose.

The results will be seen as a triumph, but also come off the back of Pfizer and Moderna showing 95% protection.

However, the Oxford jab is far cheaper, and is easier to store and get to every corner of the world than the other two.

So the vaccine will play a significant role in tackling the pandemic, if it is approved for use by regulators.

"The announcement today takes us another step closer to the time when we can use vaccines to bring an end to the devastation caused by [the virus]," said the vaccine's architect Prof Sarah Gilbert.

The UK government has pre-ordered 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine and AstraZeneca says it will make three billion doses for the world next year.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said it was "incredibly exciting news" and that while there were still safety checks to come, "these are fantastic results".

The vaccine has been developed in around 10 months, a process that normally takes a decade.

What did the trial show?

More than 20,000 volunteers were involved, half in the UK, the rest in Brazil.

There were 30 cases of Covid in people who had two doses of the vaccine and 101 cases in people who received a dummy injection.

- WHOOP-DE-DO

An entire 20,000 people

Think I will wait for a lot more testing

Suggest vaccine is tested on murderers, rapists, pedophiles, pimps and drug dealers

All of the above are expendable

Much rather drugs tested on them and NOT innocent animals

When volunteers were given two "high" doses the protection was 62%, but this rose to 90% when people were given a "low" dose followed by a high one. It's not clear why there is a difference.

"We're really pleased with these results," Prof Andrew Pollard, the trial's lead investigator, told the BBC.

He said the 90% effectiveness data was "intriguing" and would mean "we would have a lot more doses to distribute."

There were also lower levels of asymptomatic infection in the low-followed-by-high-dose group which "means we might be able to halt the virus in its tracks," Prof Pollard said.

When will I get it?

In the UK there are four million doses ready to go, with another 96 million to be delivered.

But nothing can happen until the vaccine has been approved by regulators who will assess the vaccine's safety, effectiveness, and that it is manufactured to high standard. This process will happen in the coming weeks.

However, the UK is ready to press the go button on an unprecedented mass immunisation campaign that dwarfs either the annual flu or childhood vaccination programmes.

Care home residents and staff will be first in the queue, followed by healthcare workers and the over-80s. The plan is to then to work down through the age groups.

How does it work?

The vaccine is a genetically modified common cold virus that used to infect chimpanzees.

It has been altered to stop it causing an infection in people and to carry the blueprints for part of the coronavirus, known as the spike protein.

Once these blueprints are inside the body they start the producing the coronavirus' spike protein, which the immune system recognizes as a threat and tries to squash it.

How the coronavirus vaccine works:

- The vaccine is made from a weakened version of a common cold virus (known as an adenovirus) from chimpanzees that has been modified so it cannot grow in humans.

Scientists then added genes for the spike surface protein of the coronavirus. This should prompt the immune system to produce neutralising antibodies, which would recognise and prevent any future coronavirus infection.

When the immune system comes into contact with the virus for real, it now knows what to do.

After Pfizer and Moderna both produced vaccines delivering 95% protection from Covid-19, a figure of 70% will be seen by some as relatively disappointing.

However, anything above 50% would have been considered a triumph just a month ago and 70% is comfortably better than the seasonal flu jab.

This is still a vaccine that can save lives from Covid-19.

It also has crucial advantages that make it easier to use. It can be stored at fridge temperature, which means it can be distributed to every corner of the world, unlike the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, which need to be stored at much colder temperatures.

Oxford's manufacturing partner, AstraZeneca, is preparing to make three billion doses worldwide.

The Oxford vaccine, at a price of around £3, also costs far less than Pfizer's (around £15) or Moderna's (£25) vaccines.

What difference will this make to my life?

A vaccine is what we've spent the year waiting for and what lockdowns have bought time for.

However, producing enough vaccine and then immunising tens of millions of people in the UK, and billions around the world, is still a gargantuan challenge.

Life will not return to normal tomorrow, but the situation could improve dramatically as those most at risk are protected.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told BBC Breakfast we would be "something closer to normal" by the summer but "until we can get that vaccine rolled out, we all need to look after each other".

What's the reaction been?

Prof Peter Horby, from the University of Oxford by not involved in the trial, said: "This is very welcome news, we can clearly see the end of tunnel now. There were no Covid hospitalisations or deaths in people who got the Oxford vaccine."

Dr Stephen Griffin, from the University of Leeds, said: "This is yet more excellent news and should be considered tremendously exciting. It has great potential to be delivered across the globe, achieving huge public health benefits.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55040635

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 28437

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advic

Oxford/AstraZeneca

vaccine dose error

On Monday, the world heard how the UK's Covid vaccine - from AstraZeneca and Oxford University - was highly effective in advanced trials

It gave hope of another new jab to fight the pandemic that should be cheaper and easier to distribute than the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines that announced similarly impressive results just days before.

But after the jubilation, some negative press has followed.

On Thursday, multiple news outlets in the UK and US reported that there were questions over the data. They weren't about safety, but rather how effective the jab is.

The questions centre around efficacy levels.

Three were reported from the trial - an overall efficacy of 70%, a lower one of 62% and a high of 90%.

That's because different doses of the vaccine were mistakenly used in the trial. Some volunteers were given shots half the planned strength, in error. Yet that "wrong" dose turned out to be a winner.

What does that mean?

Some of the shots were weaker than they were designed to be, containing much less of the ingredient that is meant to give a person immunity.

The jab is actually two shots, with the second given a month after the first as a booster.

While most of the volunteers in the trial got the correct dose for both of their two shots, some didn't.

Regulators were told about the error early on and they agreed that the trial could continue and more volunteers could be immunised.

The error had no effect on vaccine safety.

What were the results?

About 3,000 participants were given the half dose and then a full dose four weeks later, and this regime appeared to provide the most protection or efficacy in the trial - around 90%.

In the larger group of nearly 9,000 volunteers, who were given two full doses also four weeks apart, efficacy was 62%.

AstraZeneca reported these percentages and also said that its vaccine was, on average, 70% effective at preventing Covid-19 illness. The figures left some experts scratching their head.

Prof David Salisbury, immunisation expert and associate fellow of the global health program at the Chatham House think tank, said: "You've taken two studies for which different doses were used and come up with a composite that doesn't represent either of the doses. I think many people are having trouble with that.″

AstraZeneca stressed that the data are preliminary, rather than full and final - which is true for the reported Pfizer and Moderna jab results too. It is science by press release.

When they can, all of the companies will publish full results in medical journals for public scrutiny.

And they are submitting full data to regulators to apply for emergency approval so that countries can start using these three different vaccines to immunise whole populations.

Does it change anything?

The US regulator, called the FDA, have said any Covid vaccine needs to be at least 50% effective to be useful in fighting the pandemic.

Even if you take the lowest figure of effectiveness for the AstraZeneca jab, it still passes that benchmark.

The efficacy analysis was based on 131 cases of Covid-19 that occurred in the study participants:

One idea is that a low then high dose shot may be a better mimic of a coronavirus infection and lead to a better immune response.

But it is possible that the volunteers who got the half doses are somewhat different to those who got two big shots.

Moncef Slaoui, the scientific head of the US's Operation Warp Speed - the programme to supply America with vaccines - told US reporters that the half-dose group only included people younger than 55.

Since age is the biggest risk factor for getting seriously ill with Covid-19, a vaccine that protects the elderly is extremely important.

However, results from an earlier phase two study of the Oxford vaccine, published in The Lancet medical journal, showed the vaccine produced a strong response in all age groups.

AstraZeneca said: "The studies were conducted to the highest standards.

"More data will continue to accumulate and additional analysis will be conducted refining the efficacy reading and establishing the duration of protection."

The company said it would run a new study to evaluate a lower dosage that performed better.

Its chief executive Pascal Soriot said it would probably be another "international study, but this one could be faster because we know the efficacy is high so we need a smaller number of patients".

What do other experts say?

Although the dosing was different, the rest of the study didn't change from the original plan.

Prof Peter Openshaw, an expert at Imperial College London, says the take home message should be that we have three very promising Covid vaccines that could soon become available to help save lives.

"We have to wait for the full data and to see how the regulators view the results.

"All we have to go on is a limited data release. The protection from the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine may be less than that from the mRNA vaccines, but we need to wait and see.

"It is remarkable that each of the trials that are now reporting shows protection, which we did not know was going to be possible."

He added: "We have been wanting vaccines for many diseases for a long time and they haven't arrived - HIV, TB and malaria being good examples.

"The results so far seem to show that it can be done for Covid-19, and that's very good news indeed."

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55086927

vaccine dose error

On Monday, the world heard how the UK's Covid vaccine - from AstraZeneca and Oxford University - was highly effective in advanced trials

It gave hope of another new jab to fight the pandemic that should be cheaper and easier to distribute than the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines that announced similarly impressive results just days before.

But after the jubilation, some negative press has followed.

On Thursday, multiple news outlets in the UK and US reported that there were questions over the data. They weren't about safety, but rather how effective the jab is.

The questions centre around efficacy levels.

Three were reported from the trial - an overall efficacy of 70%, a lower one of 62% and a high of 90%.

That's because different doses of the vaccine were mistakenly used in the trial. Some volunteers were given shots half the planned strength, in error. Yet that "wrong" dose turned out to be a winner.

What does that mean?

Some of the shots were weaker than they were designed to be, containing much less of the ingredient that is meant to give a person immunity.

The jab is actually two shots, with the second given a month after the first as a booster.

While most of the volunteers in the trial got the correct dose for both of their two shots, some didn't.

Regulators were told about the error early on and they agreed that the trial could continue and more volunteers could be immunised.

The error had no effect on vaccine safety.

What were the results?

About 3,000 participants were given the half dose and then a full dose four weeks later, and this regime appeared to provide the most protection or efficacy in the trial - around 90%.

In the larger group of nearly 9,000 volunteers, who were given two full doses also four weeks apart, efficacy was 62%.

AstraZeneca reported these percentages and also said that its vaccine was, on average, 70% effective at preventing Covid-19 illness. The figures left some experts scratching their head.

Prof David Salisbury, immunisation expert and associate fellow of the global health program at the Chatham House think tank, said: "You've taken two studies for which different doses were used and come up with a composite that doesn't represent either of the doses. I think many people are having trouble with that.″

AstraZeneca stressed that the data are preliminary, rather than full and final - which is true for the reported Pfizer and Moderna jab results too. It is science by press release.

When they can, all of the companies will publish full results in medical journals for public scrutiny.

And they are submitting full data to regulators to apply for emergency approval so that countries can start using these three different vaccines to immunise whole populations.

Does it change anything?

The US regulator, called the FDA, have said any Covid vaccine needs to be at least 50% effective to be useful in fighting the pandemic.

Even if you take the lowest figure of effectiveness for the AstraZeneca jab, it still passes that benchmark.

The efficacy analysis was based on 131 cases of Covid-19 that occurred in the study participants:

- 101 of these cases happened in people who received dummy injections (either a saline jab or a meningitis vaccine).

The other 30 were in people who received the real jab - three who got the half-strength initial dose and 27 who had the two full doses.

One idea is that a low then high dose shot may be a better mimic of a coronavirus infection and lead to a better immune response.

But it is possible that the volunteers who got the half doses are somewhat different to those who got two big shots.

Moncef Slaoui, the scientific head of the US's Operation Warp Speed - the programme to supply America with vaccines - told US reporters that the half-dose group only included people younger than 55.

Since age is the biggest risk factor for getting seriously ill with Covid-19, a vaccine that protects the elderly is extremely important.

However, results from an earlier phase two study of the Oxford vaccine, published in The Lancet medical journal, showed the vaccine produced a strong response in all age groups.

AstraZeneca said: "The studies were conducted to the highest standards.

"More data will continue to accumulate and additional analysis will be conducted refining the efficacy reading and establishing the duration of protection."

The company said it would run a new study to evaluate a lower dosage that performed better.

Its chief executive Pascal Soriot said it would probably be another "international study, but this one could be faster because we know the efficacy is high so we need a smaller number of patients".

What do other experts say?

Although the dosing was different, the rest of the study didn't change from the original plan.

Prof Peter Openshaw, an expert at Imperial College London, says the take home message should be that we have three very promising Covid vaccines that could soon become available to help save lives.

"We have to wait for the full data and to see how the regulators view the results.

"All we have to go on is a limited data release. The protection from the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine may be less than that from the mRNA vaccines, but we need to wait and see.

"It is remarkable that each of the trials that are now reporting shows protection, which we did not know was going to be possible."

He added: "We have been wanting vaccines for many diseases for a long time and they haven't arrived - HIV, TB and malaria being good examples.

"The results so far seem to show that it can be done for Covid-19, and that's very good news indeed."

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55086927

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 28437

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advic

End of the Pandemic

Is Now in Sight

A year of scientific uncertainty is over. Two vaccines look like they will work, and more should follow

For all that scientists have done to tame the biological world, there are still things that lie outside the realm of human knowledge. The coronavirus was one such alarming reminder, when it emerged with murky origins in late 2019 and found naive, unwitting hosts in the human body.

Even as science began to unravel many of the virus’s mysteries—how it spreads, how it tricks its way into cells, how it kills—a fundamental unknown about vaccines hung over the pandemic and our collective human fate: Vaccines can stop many, but not all, viruses. Could they stop this one?

The answer, we now know, is yes. A resounding yes. Pfizer and Moderna have separately released preliminary data that suggest their vaccines are both more than 90 percent effective, far more than many scientists expected.

Neither company has publicly shared the full scope of their data, but independent clinical-trial monitoring boards have reviewed the results, and the FDA will soon scrutinize the vaccines for emergency use authorization. Unless the data take an unexpected turn, initial doses should be available in December.

The tasks that lie ahead—manufacturing vaccines at scale, distributing them via a cold or even ultracold chain, and persuading wary Americans to take them—are not trivial, but they are all within the realm of human knowledge.

The most tenuous moment is over: The scientific uncertainty at the heart of COVID-19 vaccines is resolved. Vaccines work. And for that, we can breathe a collective sigh of relief. “It makes it now clear that vaccines will be our way out of this pandemic,” says Kanta Subbarao, a virologist at the Doherty Institute, who has studied emerging viruses.

The invention of vaccines against a virus identified only 10 months ago is an extraordinary scientific achievement. They are the fastest vaccines ever developed, by a margin of years. From virtually the day Chinese scientists shared the genetic sequence of a new coronavirus in January, researchers began designing vaccines that might train the immune system to recognize the still-unnamed virus. They needed to identify a suitable piece of the virus to turn into a vaccine, and one promising target was the spike-shaped proteins that decorate the new virus’s outer shell.

Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines both rely on the spike protein, as do many vaccine candidates still in development. These initial successes suggest this strategy works; several more COVID-19 vaccines may soon cross the finish line. To vaccinate billions of people across the globe and bring the pandemic to a timely end, we will need all the vaccines we can get.

But it is no accident or surprise that Moderna and Pfizer are first out of the gate. They both bet on a new and hitherto unproven idea of using mRNA, which has the long-promised advantage of speed. This idea has now survived a trial by pandemic and emerged likely triumphant. If mRNA vaccines help end the pandemic and restore normal life, they may also usher in a new era for vaccine development.

The human immune system is awesome in its power, but an untrained one does not know how to aim its fire. That’s where vaccines come in. They present a harmless snapshot of a pathogen, a “wanted” poster, if you will, that primes the immune system to recognize the real virus when it comes along.

Traditionally, this snapshot could be in the form of a weakened virus or an inactivated virus or a particularly distinctive viral molecule. But those approaches require vaccine makers to manufacture viruses and their molecules, which takes time and expertise. Both are lacking during a pandemic caused by a novel virus.

mRNA vaccines offer a clever shortcut. We humans don’t need to intellectually work out how to make viruses; our bodies are already very, very good at incubating them. When the coronavirus infects us, it hijacks our cellular machinery, turning our cells into miniature factories that churn out infectious viruses.

The mRNA vaccine makes this vulnerability into a strength. What if we can trick our own cells into making just one individually harmless, though very recognizable, viral protein? The coronavirus’s spike protein fits this description, and the instructions for making it can be encoded into genetic material called mRNA.

Both vaccines, from Moderna and from Pfizer’s collaboration with the smaller German company BioNTech, package slightly modified spike-protein mRNA inside a tiny protective bubble of fat. Human cells take up this bubble and simply follow the directions to make spike protein. The cells then display these spike proteins, presenting them as strange baubles to the immune system. Recognizing these viral proteins as foreign, the immune system begins building an arsenal to prepare for the moment a virus bearing this spike protein appears.

This overall process mimics the steps of infection better than some traditional vaccines, which suggests that mRNA vaccines may provoke a better immune response for certain diseases. When you inject vaccines made of inactivated viruses or viral pieces, they can’t get inside the cell, and the cell can’t present those viral pieces to the immune system.

Those vaccines can still elicit proteins called antibodies, which neutralize the virus, but they have a harder time stimulating T cells, which make up another important part of the immune response. (Weakened viruses used in vaccines can get inside cells, but risk causing an actual infection if something goes awry. mRNA vaccines cannot cause infection because they do not contain the whole virus.)

Moreover, inactivated viruses or viral pieces tend to disappear from the body within a day, but mRNA vaccines can continue to produce spike protein for two weeks, says Drew Weissman, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania, whose mRNA vaccine research has been licensed by both BioNTech and Moderna. The longer the spike protein is around, the better for an immune response.

All of this is how mRNA vaccines should work in theory. But no one on Earth, until last week, knew whether mRNA vaccines actually do work in humans for COVID-19. Although scientists had prototyped other mRNA vaccines before the pandemic, the technology was still new.

None had been put through the paces of a large clinical trial. And the human immune system is notoriously complicated and unpredictable. Immunology is, as my colleague Ed Yong has written, where intuition goes to die. Vaccines can even make diseases more severe, rather than less.

The data from these large clinical trials from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are the first, real-world proof that mRNA vaccines protect against disease as expected. The hope, in the many years when mRNA vaccine research flew under the radar, was that the technology would deliver results quickly in a pandemic. And now it has.

“What a relief,” says Barney Graham, a virologist at the National Institutes of Health, who helped design the spike protein for the Moderna vaccine. “You can make thousands of decisions, and thousands of things have to go right for this to actually come out and work. You’re just worried that you have made some wrong turns along the way.”

For Graham, this vaccine is a culmination of years of such decisions, long predating the discovery of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. He and his collaborators had homed in on the importance of spike protein in another virus, called respiratory syncytial virus, and figured out how to make the protein more stable and thus suitable for vaccines. This modification appears in both Pfizer/BioNTech’s and Moderna’s vaccines, as well as other leading vaccine candidates.

The spectacular efficacy of these vaccines, should the preliminary data hold, likely also has to do with the choice of spike protein as vaccine target. On one hand, scientists were prepared for the spike protein, thanks to research like Graham’s. On the other hand, the coronavirus’s spike protein offered an opening. Three separate components of the immune system—antibodies, helper cells, and killer T cells—all respond to the spike protein, which isn’t the case with most viruses.

In this, we were lucky. “It’s the three punches,” says Alessandro Sette. Working with Shane Crotty, his fellow immunologist at the La Jolla Institute, Sette found that COVID-19 patients whose immune systems can marshal all three responses against the spike protein tend to fare the best.

The fact that most people can recover from COVID-19 was always encouraging news; it meant a vaccine simply needed to jump-start the immune system, which could then take on the virus itself. But no definitive piece of evidence existed that proved COVID-19 vaccines would be a slam dunk. “There’s nothing like a Phase 3 clinical trial,” Crotty says. “You don’t know what’s gonna happen with a vaccine until it happens, because the virus is complicated and the immune system is complicated.”

Experts anticipate that the ongoing trials will clarify still-unanswered questions about the COVID-19 vaccines. For example, Ruth Karron, the director of the Center for Immunization Research at Johns Hopkins University, asks, does the vaccine prevent only a patient’s symptoms? Or does it keep them from spreading the virus?

How long will immunity last? How well does it protect the elderly, many of whom have a weaker response to the flu vaccine? So far, Pfizer has noted that its vaccine seems to protect the elderly just as well, which is good news because they are especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

Several more vaccines using the spike protein are in clinical trials too. They rely on a suite of different vaccine technologies, including weakened viruses, inactivated viruses, viral proteins, and another fairly new concept called DNA vaccines. Never before have companies tested so many different types of vaccines against the same virus, which might end up revealing something new about vaccines in general.

You now have the same spike protein delivered in many different ways, Sette points out. How will the vaccines behave differently? Will they each stimulate different parts of the immune system? And which parts are best for protecting against the coronavirus? The pandemic is an opportunity to compare different types of vaccines head-on.

If the two mRNA vaccines continue to be as good as they initially seem, their success will likely crack open a whole new world of mRNA vaccines. Scientists are already testing them against currently un-vaccinable viruses such as Zika and cytomegalovirus and trying to make improved versions of existing vaccines, such as for the flu. Another possibility lies in personalized mRNA vaccines that can stimulate the immune system to fight cancer.

But the next few months will be a test of one potential downside of mRNA vaccines: their extreme fragility. mRNA is an inherently unstable molecule, which is why it needs that protective bubble of fat, called a lipid nanoparticle. But the lipid nanoparticle itself is exquisitely sensitive to temperature.

For longer-term storage, Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine has to be stored at –70 degrees Celsius and Moderna’s at –20 Celsius, though they can be kept at higher temperatures for a shorter amount of time. Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have said they can collectively supply enough doses for 22.5 million people in the United States by the end of the year.

Distributing the limited vaccines fairly and smoothly will be a massive political and logistical challenge, especially as it begins during a bitter transition of power in Washington. The vaccine is a scientific triumph, but the past eight months have made clear how much pandemic preparedness is not only about scientific research.

Ensuring adequate supplies of tests and personal protective equipment, providing economic relief, and communicating the known risks of COVID-19 transmission are all well within the realm of human knowledge, yet the U.S. government has failed at all of that.

The vaccine by itself cannot slow the dangerous trajectory of COVID-19 hospitalizations this fall or save the many people who may die by Christmas. But it can give us hope that the pandemic will end. Every infection we prevent now—through masking and social distancing—is an infection that can, eventually, be prevented forever through vaccines.

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/arch ... obal-en-GB

Is Now in Sight

A year of scientific uncertainty is over. Two vaccines look like they will work, and more should follow

For all that scientists have done to tame the biological world, there are still things that lie outside the realm of human knowledge. The coronavirus was one such alarming reminder, when it emerged with murky origins in late 2019 and found naive, unwitting hosts in the human body.

Even as science began to unravel many of the virus’s mysteries—how it spreads, how it tricks its way into cells, how it kills—a fundamental unknown about vaccines hung over the pandemic and our collective human fate: Vaccines can stop many, but not all, viruses. Could they stop this one?

The answer, we now know, is yes. A resounding yes. Pfizer and Moderna have separately released preliminary data that suggest their vaccines are both more than 90 percent effective, far more than many scientists expected.

Neither company has publicly shared the full scope of their data, but independent clinical-trial monitoring boards have reviewed the results, and the FDA will soon scrutinize the vaccines for emergency use authorization. Unless the data take an unexpected turn, initial doses should be available in December.

The tasks that lie ahead—manufacturing vaccines at scale, distributing them via a cold or even ultracold chain, and persuading wary Americans to take them—are not trivial, but they are all within the realm of human knowledge.

The most tenuous moment is over: The scientific uncertainty at the heart of COVID-19 vaccines is resolved. Vaccines work. And for that, we can breathe a collective sigh of relief. “It makes it now clear that vaccines will be our way out of this pandemic,” says Kanta Subbarao, a virologist at the Doherty Institute, who has studied emerging viruses.

The invention of vaccines against a virus identified only 10 months ago is an extraordinary scientific achievement. They are the fastest vaccines ever developed, by a margin of years. From virtually the day Chinese scientists shared the genetic sequence of a new coronavirus in January, researchers began designing vaccines that might train the immune system to recognize the still-unnamed virus. They needed to identify a suitable piece of the virus to turn into a vaccine, and one promising target was the spike-shaped proteins that decorate the new virus’s outer shell.

Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines both rely on the spike protein, as do many vaccine candidates still in development. These initial successes suggest this strategy works; several more COVID-19 vaccines may soon cross the finish line. To vaccinate billions of people across the globe and bring the pandemic to a timely end, we will need all the vaccines we can get.

But it is no accident or surprise that Moderna and Pfizer are first out of the gate. They both bet on a new and hitherto unproven idea of using mRNA, which has the long-promised advantage of speed. This idea has now survived a trial by pandemic and emerged likely triumphant. If mRNA vaccines help end the pandemic and restore normal life, they may also usher in a new era for vaccine development.

The human immune system is awesome in its power, but an untrained one does not know how to aim its fire. That’s where vaccines come in. They present a harmless snapshot of a pathogen, a “wanted” poster, if you will, that primes the immune system to recognize the real virus when it comes along.

Traditionally, this snapshot could be in the form of a weakened virus or an inactivated virus or a particularly distinctive viral molecule. But those approaches require vaccine makers to manufacture viruses and their molecules, which takes time and expertise. Both are lacking during a pandemic caused by a novel virus.

mRNA vaccines offer a clever shortcut. We humans don’t need to intellectually work out how to make viruses; our bodies are already very, very good at incubating them. When the coronavirus infects us, it hijacks our cellular machinery, turning our cells into miniature factories that churn out infectious viruses.

The mRNA vaccine makes this vulnerability into a strength. What if we can trick our own cells into making just one individually harmless, though very recognizable, viral protein? The coronavirus’s spike protein fits this description, and the instructions for making it can be encoded into genetic material called mRNA.

Both vaccines, from Moderna and from Pfizer’s collaboration with the smaller German company BioNTech, package slightly modified spike-protein mRNA inside a tiny protective bubble of fat. Human cells take up this bubble and simply follow the directions to make spike protein. The cells then display these spike proteins, presenting them as strange baubles to the immune system. Recognizing these viral proteins as foreign, the immune system begins building an arsenal to prepare for the moment a virus bearing this spike protein appears.

This overall process mimics the steps of infection better than some traditional vaccines, which suggests that mRNA vaccines may provoke a better immune response for certain diseases. When you inject vaccines made of inactivated viruses or viral pieces, they can’t get inside the cell, and the cell can’t present those viral pieces to the immune system.

Those vaccines can still elicit proteins called antibodies, which neutralize the virus, but they have a harder time stimulating T cells, which make up another important part of the immune response. (Weakened viruses used in vaccines can get inside cells, but risk causing an actual infection if something goes awry. mRNA vaccines cannot cause infection because they do not contain the whole virus.)

Moreover, inactivated viruses or viral pieces tend to disappear from the body within a day, but mRNA vaccines can continue to produce spike protein for two weeks, says Drew Weissman, an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania, whose mRNA vaccine research has been licensed by both BioNTech and Moderna. The longer the spike protein is around, the better for an immune response.

All of this is how mRNA vaccines should work in theory. But no one on Earth, until last week, knew whether mRNA vaccines actually do work in humans for COVID-19. Although scientists had prototyped other mRNA vaccines before the pandemic, the technology was still new.

None had been put through the paces of a large clinical trial. And the human immune system is notoriously complicated and unpredictable. Immunology is, as my colleague Ed Yong has written, where intuition goes to die. Vaccines can even make diseases more severe, rather than less.

The data from these large clinical trials from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are the first, real-world proof that mRNA vaccines protect against disease as expected. The hope, in the many years when mRNA vaccine research flew under the radar, was that the technology would deliver results quickly in a pandemic. And now it has.

“What a relief,” says Barney Graham, a virologist at the National Institutes of Health, who helped design the spike protein for the Moderna vaccine. “You can make thousands of decisions, and thousands of things have to go right for this to actually come out and work. You’re just worried that you have made some wrong turns along the way.”

For Graham, this vaccine is a culmination of years of such decisions, long predating the discovery of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. He and his collaborators had homed in on the importance of spike protein in another virus, called respiratory syncytial virus, and figured out how to make the protein more stable and thus suitable for vaccines. This modification appears in both Pfizer/BioNTech’s and Moderna’s vaccines, as well as other leading vaccine candidates.

The spectacular efficacy of these vaccines, should the preliminary data hold, likely also has to do with the choice of spike protein as vaccine target. On one hand, scientists were prepared for the spike protein, thanks to research like Graham’s. On the other hand, the coronavirus’s spike protein offered an opening. Three separate components of the immune system—antibodies, helper cells, and killer T cells—all respond to the spike protein, which isn’t the case with most viruses.

In this, we were lucky. “It’s the three punches,” says Alessandro Sette. Working with Shane Crotty, his fellow immunologist at the La Jolla Institute, Sette found that COVID-19 patients whose immune systems can marshal all three responses against the spike protein tend to fare the best.

The fact that most people can recover from COVID-19 was always encouraging news; it meant a vaccine simply needed to jump-start the immune system, which could then take on the virus itself. But no definitive piece of evidence existed that proved COVID-19 vaccines would be a slam dunk. “There’s nothing like a Phase 3 clinical trial,” Crotty says. “You don’t know what’s gonna happen with a vaccine until it happens, because the virus is complicated and the immune system is complicated.”

Experts anticipate that the ongoing trials will clarify still-unanswered questions about the COVID-19 vaccines. For example, Ruth Karron, the director of the Center for Immunization Research at Johns Hopkins University, asks, does the vaccine prevent only a patient’s symptoms? Or does it keep them from spreading the virus?

How long will immunity last? How well does it protect the elderly, many of whom have a weaker response to the flu vaccine? So far, Pfizer has noted that its vaccine seems to protect the elderly just as well, which is good news because they are especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

Several more vaccines using the spike protein are in clinical trials too. They rely on a suite of different vaccine technologies, including weakened viruses, inactivated viruses, viral proteins, and another fairly new concept called DNA vaccines. Never before have companies tested so many different types of vaccines against the same virus, which might end up revealing something new about vaccines in general.

You now have the same spike protein delivered in many different ways, Sette points out. How will the vaccines behave differently? Will they each stimulate different parts of the immune system? And which parts are best for protecting against the coronavirus? The pandemic is an opportunity to compare different types of vaccines head-on.

If the two mRNA vaccines continue to be as good as they initially seem, their success will likely crack open a whole new world of mRNA vaccines. Scientists are already testing them against currently un-vaccinable viruses such as Zika and cytomegalovirus and trying to make improved versions of existing vaccines, such as for the flu. Another possibility lies in personalized mRNA vaccines that can stimulate the immune system to fight cancer.

But the next few months will be a test of one potential downside of mRNA vaccines: their extreme fragility. mRNA is an inherently unstable molecule, which is why it needs that protective bubble of fat, called a lipid nanoparticle. But the lipid nanoparticle itself is exquisitely sensitive to temperature.

For longer-term storage, Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine has to be stored at –70 degrees Celsius and Moderna’s at –20 Celsius, though they can be kept at higher temperatures for a shorter amount of time. Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have said they can collectively supply enough doses for 22.5 million people in the United States by the end of the year.

Distributing the limited vaccines fairly and smoothly will be a massive political and logistical challenge, especially as it begins during a bitter transition of power in Washington. The vaccine is a scientific triumph, but the past eight months have made clear how much pandemic preparedness is not only about scientific research.

Ensuring adequate supplies of tests and personal protective equipment, providing economic relief, and communicating the known risks of COVID-19 transmission are all well within the realm of human knowledge, yet the U.S. government has failed at all of that.

The vaccine by itself cannot slow the dangerous trajectory of COVID-19 hospitalizations this fall or save the many people who may die by Christmas. But it can give us hope that the pandemic will end. Every infection we prevent now—through masking and social distancing—is an infection that can, eventually, be prevented forever through vaccines.

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/arch ... obal-en-GB

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 28437

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advic

Are Covid-19 Vaccines 95% Effective?

You might assume that 95 out of every 100 people vaccinated will be protected from Covid-19. But that’s not how the math works

Experts say it’s easy to misconstrue early results because the language vaccine researchers use to talk about their trials can be hard for outsiders to understand.

The front-runners in the vaccine race seem to be working far better than anyone expected: Pfizer and BioNTech announced this week that their vaccine had an efficacy rate of 95 percent. Moderna put the figure for its vaccine at 94.5 percent. In Russia, the makers of the Sputnik vaccine claimed their efficacy rate was over 90 percent.

“These are game changers,” said Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccine researcher at the Mayo Clinic. “We were all expecting 50 to 70 percent.” Indeed, the Food and Drug Administration had said it would consider granting emergency approval for vaccines that showed just 50 percent efficacy.

From the headlines, you might well assume that these vaccines — which some people may receive in a matter of weeks — will protect 95 out of 100 people who get them. But that’s not actually what the trials have shown. Exactly how the vaccines perform out in the real world will depend on a lot of factors we just don’t have answers to yet — such as whether vaccinated people can get asymptomatic infections and how many people will get vaccinated.

Here’s what you need to know about the actual effectiveness of these vaccines.

What do the companies mean when they say their vaccines are 95 percent effective?

The fundamental logic behind today’s vaccine trials was worked out by statisticians over a century ago. Researchers vaccinate some people and give a placebo to others. They then wait for participants to get sick and look at how many of the illnesses came from each group.

A 95 percent efficacy is certainly compelling evidence that a vaccine works well. But that number doesn’t tell you what your chances are of becoming sick if you get vaccinated. And on its own, it also doesn’t say how well the vaccine will bring down Covid-19 across the United States.

What’s the difference between efficacy and effectiveness?

Efficacy and effectiveness are related to each other, but they’re not the same thing. And vaccine experts say it’s crucial not to mix them up. Efficacy is just a measurement made during a clinical trial. “Effectiveness is how well the vaccine works out in the real world,” said Naor Bar-Zeev, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

It’s possible that the effectiveness of coronavirus vaccines will match their impressive efficacy in clinical trials. But if previous vaccines are any guide, effectiveness may prove somewhat lower.

The mismatch comes about because the people who join clinical trials are not a perfect reflection of the population at large. Out in the real world, people may have a host of chronic health problems that could interfere with a vaccine’s protection, for example.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a long history of following the effectiveness of vaccines after they’re approved. On Thursday, the agency posted information on its website about its plans to study the effectiveness of coronavirus vaccines. It will find opportunities to compare the health of vaccinated people to others in their communities who have not received a vaccine.

What exactly are these vaccines effective at doing?

The clinical trials run by Pfizer and other companies were specifically designed to see whether vaccines protect people from getting sick from Covid-19. If volunteers developed symptoms like a fever or cough, they were then tested for the coronavirus.

But there’s abundant evidence that people can get infected with the coronavirus without ever showing symptoms. And so it’s possible that a number of people who got vaccinated in the clinical trials got infected, too, without ever realizing it. If those cases indeed exist, none of them are reflected in the 95 percent efficacy rate.

People who are asymptomatic can still spread the virus to others. Some studies suggest that they produce fewer viruses, making them less of a threat than infected people who go on to develop symptoms. But if people get vaccinated and then stop wearing masks and taking other safety measures, their chances of spreading the coronavirus to others could increase.

“You could get this paradoxical situation of things getting worse,” said Dr. Bar-Zeev.

Will these vaccines put a dent in the epidemic?

Vaccines don’t protect only the people who get them. Because they slow the spread of the virus, they can, over time, also drive down new infection rates and protect society as a whole.

Scientists call this broad form of effectiveness a vaccine’s impact. The smallpox vaccine had the greatest impact of all, driving the virus into oblivion in the 1970s. But even a vaccine with extremely high efficacy in clinical trials will have a small impact if only a few people end up getting it.

“Vaccines don’t save lives,” said A. David Paltiel, a professor at the Yale School of Public Health. “Vaccination programs save lives.”

On Thursday, Dr. Paltiel and his colleagues published a study in the journal Health Affairs in which they simulated the coming rollout of coronavirus vaccines. They modeled vaccines with efficacy rates ranging from high to low, but also considered how quickly and widely a vaccine could be distributed as the pandemic continues to rage.

The results, Dr. Paltiel said, were heartbreaking. He and his colleagues found that when it comes to cutting down on infections, hospitalizations and deaths, the deployment mattered just as much as the efficacy. The study left Dr. Paltiel worried that the United States has not done enough to prepare for the massive distribution of the vaccine in the months to come.

“Time is really running out,” he warned. “Infrastructure is going to contribute at least as much, if not more, than the vaccine itself to the success of the program.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/20/heal ... obal-en-GB

You might assume that 95 out of every 100 people vaccinated will be protected from Covid-19. But that’s not how the math works

Experts say it’s easy to misconstrue early results because the language vaccine researchers use to talk about their trials can be hard for outsiders to understand.

The front-runners in the vaccine race seem to be working far better than anyone expected: Pfizer and BioNTech announced this week that their vaccine had an efficacy rate of 95 percent. Moderna put the figure for its vaccine at 94.5 percent. In Russia, the makers of the Sputnik vaccine claimed their efficacy rate was over 90 percent.

“These are game changers,” said Dr. Gregory Poland, a vaccine researcher at the Mayo Clinic. “We were all expecting 50 to 70 percent.” Indeed, the Food and Drug Administration had said it would consider granting emergency approval for vaccines that showed just 50 percent efficacy.

From the headlines, you might well assume that these vaccines — which some people may receive in a matter of weeks — will protect 95 out of 100 people who get them. But that’s not actually what the trials have shown. Exactly how the vaccines perform out in the real world will depend on a lot of factors we just don’t have answers to yet — such as whether vaccinated people can get asymptomatic infections and how many people will get vaccinated.

Here’s what you need to know about the actual effectiveness of these vaccines.

What do the companies mean when they say their vaccines are 95 percent effective?

The fundamental logic behind today’s vaccine trials was worked out by statisticians over a century ago. Researchers vaccinate some people and give a placebo to others. They then wait for participants to get sick and look at how many of the illnesses came from each group.

- In the case of Pfizer, for example, the company recruited 43,661 volunteers and waited for 170 people to come down with symptoms of Covid-19 and then get a positive test. Out of these 170, 162 had received a placebo shot, and just eight had received the real vaccine

A 95 percent efficacy is certainly compelling evidence that a vaccine works well. But that number doesn’t tell you what your chances are of becoming sick if you get vaccinated. And on its own, it also doesn’t say how well the vaccine will bring down Covid-19 across the United States.

What’s the difference between efficacy and effectiveness?

Efficacy and effectiveness are related to each other, but they’re not the same thing. And vaccine experts say it’s crucial not to mix them up. Efficacy is just a measurement made during a clinical trial. “Effectiveness is how well the vaccine works out in the real world,” said Naor Bar-Zeev, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

It’s possible that the effectiveness of coronavirus vaccines will match their impressive efficacy in clinical trials. But if previous vaccines are any guide, effectiveness may prove somewhat lower.

The mismatch comes about because the people who join clinical trials are not a perfect reflection of the population at large. Out in the real world, people may have a host of chronic health problems that could interfere with a vaccine’s protection, for example.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a long history of following the effectiveness of vaccines after they’re approved. On Thursday, the agency posted information on its website about its plans to study the effectiveness of coronavirus vaccines. It will find opportunities to compare the health of vaccinated people to others in their communities who have not received a vaccine.

What exactly are these vaccines effective at doing?

The clinical trials run by Pfizer and other companies were specifically designed to see whether vaccines protect people from getting sick from Covid-19. If volunteers developed symptoms like a fever or cough, they were then tested for the coronavirus.

But there’s abundant evidence that people can get infected with the coronavirus without ever showing symptoms. And so it’s possible that a number of people who got vaccinated in the clinical trials got infected, too, without ever realizing it. If those cases indeed exist, none of them are reflected in the 95 percent efficacy rate.

People who are asymptomatic can still spread the virus to others. Some studies suggest that they produce fewer viruses, making them less of a threat than infected people who go on to develop symptoms. But if people get vaccinated and then stop wearing masks and taking other safety measures, their chances of spreading the coronavirus to others could increase.

“You could get this paradoxical situation of things getting worse,” said Dr. Bar-Zeev.

Will these vaccines put a dent in the epidemic?

Vaccines don’t protect only the people who get them. Because they slow the spread of the virus, they can, over time, also drive down new infection rates and protect society as a whole.

Scientists call this broad form of effectiveness a vaccine’s impact. The smallpox vaccine had the greatest impact of all, driving the virus into oblivion in the 1970s. But even a vaccine with extremely high efficacy in clinical trials will have a small impact if only a few people end up getting it.

“Vaccines don’t save lives,” said A. David Paltiel, a professor at the Yale School of Public Health. “Vaccination programs save lives.”

On Thursday, Dr. Paltiel and his colleagues published a study in the journal Health Affairs in which they simulated the coming rollout of coronavirus vaccines. They modeled vaccines with efficacy rates ranging from high to low, but also considered how quickly and widely a vaccine could be distributed as the pandemic continues to rage.

The results, Dr. Paltiel said, were heartbreaking. He and his colleagues found that when it comes to cutting down on infections, hospitalizations and deaths, the deployment mattered just as much as the efficacy. The study left Dr. Paltiel worried that the United States has not done enough to prepare for the massive distribution of the vaccine in the months to come.

“Time is really running out,” he warned. “Infrastructure is going to contribute at least as much, if not more, than the vaccine itself to the success of the program.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/20/heal ... obal-en-GB

Good Thoughts Good Words Good Deeds

-

Anthea - Shaswar

- Donator

- Posts: 28437

- Images: 1155

- Joined: Thu Oct 18, 2012 2:13 pm

- Location: Sitting in front of computer

- Highscores: 3

- Arcade winning challenges: 6

- Has thanked: 6019 times

- Been thanked: 729 times

- Nationality: Kurd by heart

Re: Coronavirus: we separate myths from facts and give advic

Covid-19: Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine

safe for use in UK from next week

The UK has become the first country in the world to approve the Pfizer/BioNTech coronavirus vaccine, paving the way for mass vaccination

The first doses are already on their way to the UK, with 800,000 due in the coming days, Pfizer said.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said the NHS will contact people about jabs.

Elderly people in care homes and care home staff have been placed top of the priority list, followed by over-80s and health and care staff.

But because hospitals already have the facilities to store the vaccine at -70C, as required, the very first vaccinations are likely to take place there - for care home staff, NHS staff and patients - so none of the vaccine is wasted.

The Pfizer/BioNTech jab is the fastest vaccine to go from concept to reality, taking only 10 months to follow the same steps that normally span 10 years.

The UK has already ordered 40 million doses of the jab - enough to vaccinate 20 million people.

The doses will be rolled out as quickly as they can be made by Pfizer in Belgium, Mr Hancock said, with the first load next week and then "several millions" throughout December.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said the first people in Scotland will be immunised on Tuesday.

The bulk of the rollout will be next year, Mr Hancock said. "2020 has been just awful and 2021 is going to be better," he said.

"I'm confident now, with the news today, that from spring, from Easter onwards, things are going to be better. And we're going to have a summer next year that everybody can enjoy."

Prime Minister Boris Johnson added: "It's the protection of vaccines that will ultimately allow us to reclaim our lives and get the economy moving again."

media captionHeath Secretary Matt Hancock says he is "thrilled" that the vaccine has been approved

The free vaccine will not be compulsory and there will be three ways of vaccinating people across the UK:

It is thought the vaccination network could start delivering more than one million doses a week once enough doses are available.

NHS chief executive Sir Simon Stevens said the health service was preparing for "the largest-scale vaccination campaign in our country's history".

But experts said people still need to remain vigilant and follow rules to stop the virus spreading - including with social distancing, face masks and self-isolation.

"We can't lower our guard yet," said the government's chief medical adviser Prof Chris Whitty.

This is the news we have all been waiting for

Analysis box by Nick Triggle, health correspondent

This is the news we have all been waiting for.

The NHS has already been gearing up for this moment for some time. The venues are in place and there is provision for extra staffing, with even lifeguards and airline staff to be brought in to help with the effort.

But the biggest hurdle will be supply.

The UK has been promised 40 million doses by the spring - enough to give the required two jabs to health and care workers and everyone over 65. But in the first few weeks of winter, our ability to vaccinate could easily outstrip supply.

Ministers say they will have 800,000 doses in the country within days - with several million more to follow in weeks - but the original expectation that there could be 10 million doses by the end of the year is already looking ambitious.

Getting the jabs into the country remains a challenge. It is being made in Belgium. Could Brexit be an issue? The government is confident it has secure routes to ensure supply does not get disrupted.

Nonetheless, major hopes are still being pinned to authorisation being given to the Oxford University vaccine so that rollout can happen as quickly as possible in 2021.

The order in which people will get the jab is decided by the Joint Committee on Vaccinations and Immunisations.

Mass immunisation of everyone over 50, as well as younger people with pre-existing health conditions, can happen as more stocks become available in 2021.

The vaccine is given as two injections, 21 days apart, with the second dose being a booster. Immunity begins to kick in after the first dose but reaches its full effect seven days after the second dose.

Most of the side effects are very mild, similar to the side effects after any other vaccine and usually last for a day or so, said Prof Sir Munir Pirmohamed, the chairman of the Commission on Human Medicine expert working group.

The vaccine was 95% effective for all groups in the trials, including elderly people, he said.

The head of the MHRA, Dr June Raine, said despite the speed of approval, no corners have been cut.

Batches of the vaccine will be tested in labs "so that every single vaccine that goes out meets the same high standards of safety", she said.

media captionDr June Raine from the MHRA: "The safety of the public will always come first"

Giving the analogy of climbing a mountain, she said: "If you're climbing a mountain, you prepare and prepare. We started that in June. By the time the interim results became available on 10 November we were at base camp.

"And then when we got the final analysis we were ready for that last sprint that takes us to today."

The Pfizer/BioNTech was the first vaccine to publish positive early results from final stages of testing.

It is a new type called an mRNA vaccine that uses a tiny fragment of genetic code from the pandemic virus to teach the body how to fight Covid-19 and build immunity.

An mRNA vaccine has never been approved for use in humans before, although people have received them in clinical trials.

Because the vaccine must be stored at around -70C, it will be transported in special boxes of up to 5,000 doses, packed in dry ice.

Once delivered, it can be kept for up to five days in a fridge. And once out of the fridge it needs to be used within six hours.

There are some other promising vaccines that could also be approved soon.

One from Moderna uses the same mRNA approach as the Pfizer vaccine and offers similar protection. The UK has pre-ordered seven million doses that could be ready by the spring.

The UK has ordered 100 million doses of a different type of Covid vaccine from Oxford University and AstraZeneca. That vaccine uses a harmless virus, altered to look a lot more like the virus that causes Covid-19.

Russia has been using another vaccine, called Sputnik, and the Chinese military has approved another one made by CanSino Biologics. Both work in a similar way to the Oxford vaccine

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55145696

safe for use in UK from next week

The UK has become the first country in the world to approve the Pfizer/BioNTech coronavirus vaccine, paving the way for mass vaccination

- NOT IN MY ARM

The first doses are already on their way to the UK, with 800,000 due in the coming days, Pfizer said.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said the NHS will contact people about jabs.

Elderly people in care homes and care home staff have been placed top of the priority list, followed by over-80s and health and care staff.

But because hospitals already have the facilities to store the vaccine at -70C, as required, the very first vaccinations are likely to take place there - for care home staff, NHS staff and patients - so none of the vaccine is wasted.

The Pfizer/BioNTech jab is the fastest vaccine to go from concept to reality, taking only 10 months to follow the same steps that normally span 10 years.

The UK has already ordered 40 million doses of the jab - enough to vaccinate 20 million people.

The doses will be rolled out as quickly as they can be made by Pfizer in Belgium, Mr Hancock said, with the first load next week and then "several millions" throughout December.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said the first people in Scotland will be immunised on Tuesday.

The bulk of the rollout will be next year, Mr Hancock said. "2020 has been just awful and 2021 is going to be better," he said.

"I'm confident now, with the news today, that from spring, from Easter onwards, things are going to be better. And we're going to have a summer next year that everybody can enjoy."

Prime Minister Boris Johnson added: "It's the protection of vaccines that will ultimately allow us to reclaim our lives and get the economy moving again."

media captionHeath Secretary Matt Hancock says he is "thrilled" that the vaccine has been approved

The free vaccine will not be compulsory and there will be three ways of vaccinating people across the UK:

- Hospitals

in the community, with GPs and pharmacists

Vaccination centres a bit like the Nightingales project and including some of the Nightingales